Dead as a dodo

Back in March, my second big book was published after many months of tapping away at my Remington typewriter and begging some kindly illustrators to help me with pictures, for which they were remunerated in charcoal and easels. The book is all about extinct animals, namely the ones that have disappeared in the time that the line which gave rise to us diverged from the other primates, so a few million years. Here is the cover of the book:

I didn’t choose this picture, but it’s supposed to be a diprotodon and its babies. It’s not the best picture I’ve seen of these giant, long-dead marsupials, but when I look at the big, stupid face of the adult I can’t help feeling a pang of sadness that this animal and many other interesting creatures are no longer around. Most of the animals in this book have something in common. The observant among you will note they’re all very dead indeed, but the second thing they share is the fact that humans played a part in their downfall. For some species, e.g. the Carolina parakeet and the Stephens Island wren there is no dispute that humans wiped them out. For other species, academics argue until they’re blue in the face with their spectacles at the end of their noses that humans did or did not have a hand in their extinction. We’ll never know for sure what caused the extinction of animals like the Sivathere or elasmotherium because they disappeared before humans invented pens and paper and even stone tablets and chisels. Thanks to this lack of any first hand evidence academics will be arguing the toss until their dispute grants run out.

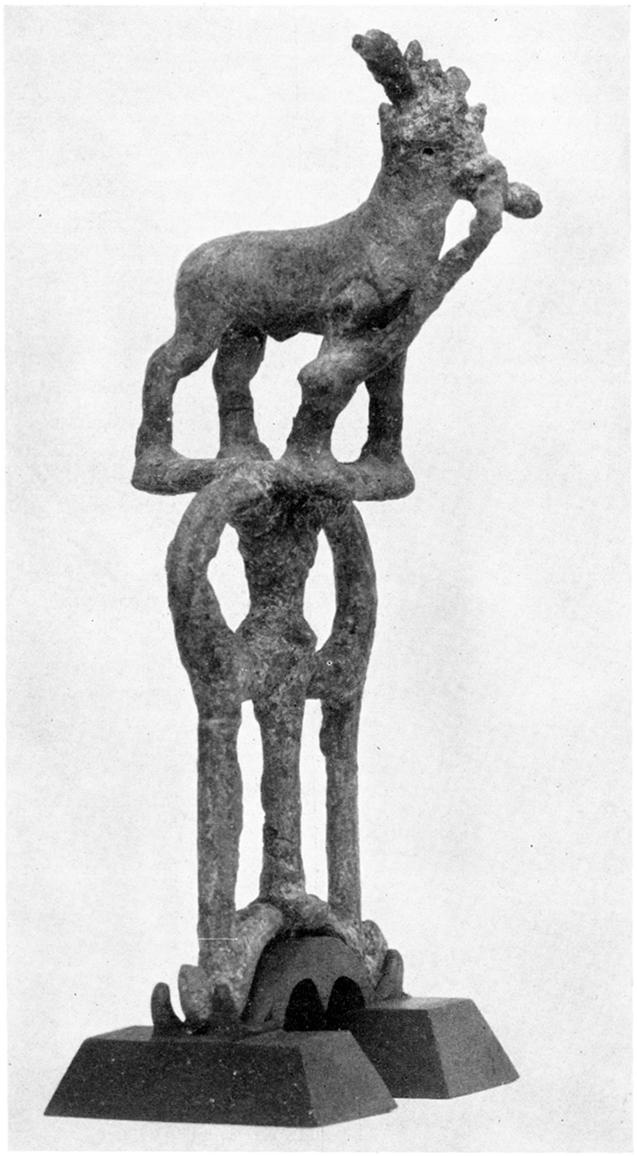

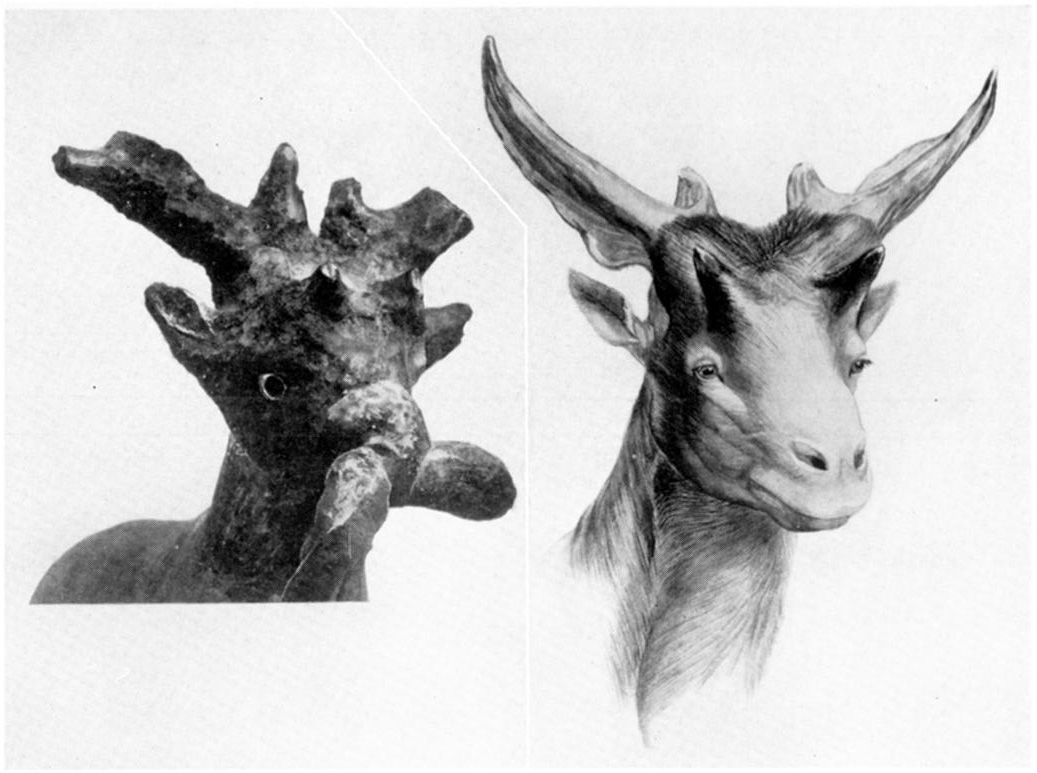

Anyway, let’s take a look at some of the animals in the book. First up is the Sivathere because there’s some tantalising evidence that it survived into the times when early civilisations were getting stuff down on bits of rock. The civilization in question is the Sumerian and in the 1920s an archaeological expedition to Kish, in modern day Iraq, found some very interesting artefacts, one of which was a rein-ring fashioned from copper. Rein rein-rings made from copper and of this age aren’t all that special, but what made this one stand out was the little animal surmounting the artefact. Initially, it was thought to represent a stag, but if you take a look (see below), the proportions are all wrong and the close-up of the head looks like no deer alive or dead. Above each eye is a small horn and the ‘antlers’ are all wrong.

Granted, the rein-ring is not in perfect condition, but it’s definitely not a stag. The only animal it looks like, alive or dead, is a Sivathere: big, thick-set relatives of modern-day giraffes that were thought to have become extinct about 150000 years ago. Is it possible a species of Sivathere survived until it at least 3500 BC? Does the sculpture depict an animal that was known to the Sumerians or is it nothing more than the product of a metalworker’s sun-addled imagination? The mystery animal doesn’t seem to be fantastical enough to be the product of someone’s imagination and the bodily proportions and features of the head suggest whoever sculpted this animal had seen this creature first hand. Furthermore and more tantalizing still is the heavy rope attached to the mystery beast’s snout. Perhaps the inspiration for the sculptor’s work was an animal that had been caught and held captive by the Sumerians?

Stephens Island wren holds the unfortunate titles of being the only known species that has been wiped out by a domestic cat and the only animal that has gone from discovery to extinction in a little more than year. The animals introduced to New Zealand by Pacific islanders had exterminated this tiny, almost flightless bird from the big islands of this archipelago and by the time European reached these lands it was found only on Stephens Island. The powers that be thought the island needed a lighthouse, so it got one and with the lighthouse came a lighthouse keeper, closely followed by a pregnant cat – the first mammalian predator to set foot on this tiny island and the nemesis of Stephens Island wren. The tiny defenceless bird didn’t know what a cat was let alone how to escape from one, so the end for this species came very quickly.

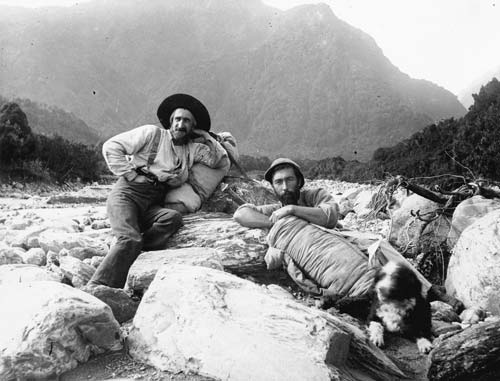

Still in New Zealand and still with the birds, Haast’s eagle was probably the largest eagle that has ever lived. Sadly, size isn’t everything and it preceded the Stephens Island wren onto the roll-call of extinction. This massive bird was a specialist predator of moa, the giant, flightless birds of New Zealand and it probably hunted them by slamming into their hindquarters after a short dive as moa pelvic bones bearing deep scars attest. Sadly, the eagle’s monopoly over the peaceful, vegetarian moa was broken by the arrival of humans in around 1300 AD. Humans hunted the moa and destroyed their habitats until every species was extinct and it seems that with its prey gone the eagle was doomed. With that said, this massive eagle may have survived into more recent times according to the journal of famous New Zealand explorer – Charles Douglas who claimed to have seen two huge birds of prey in an isolated part of the Landsborough River valley in South Island. Unfortunately, we’ll never know the truth as both birds ended up in Douglas’ belly after he shot and cooked them. If these mysterious birds were really Haast’s eagles then, it appears, this impressive species met its end as the main course of a bearded Victorian explorer. I think you’ll agree that’ quite an ignominious ending for any species.

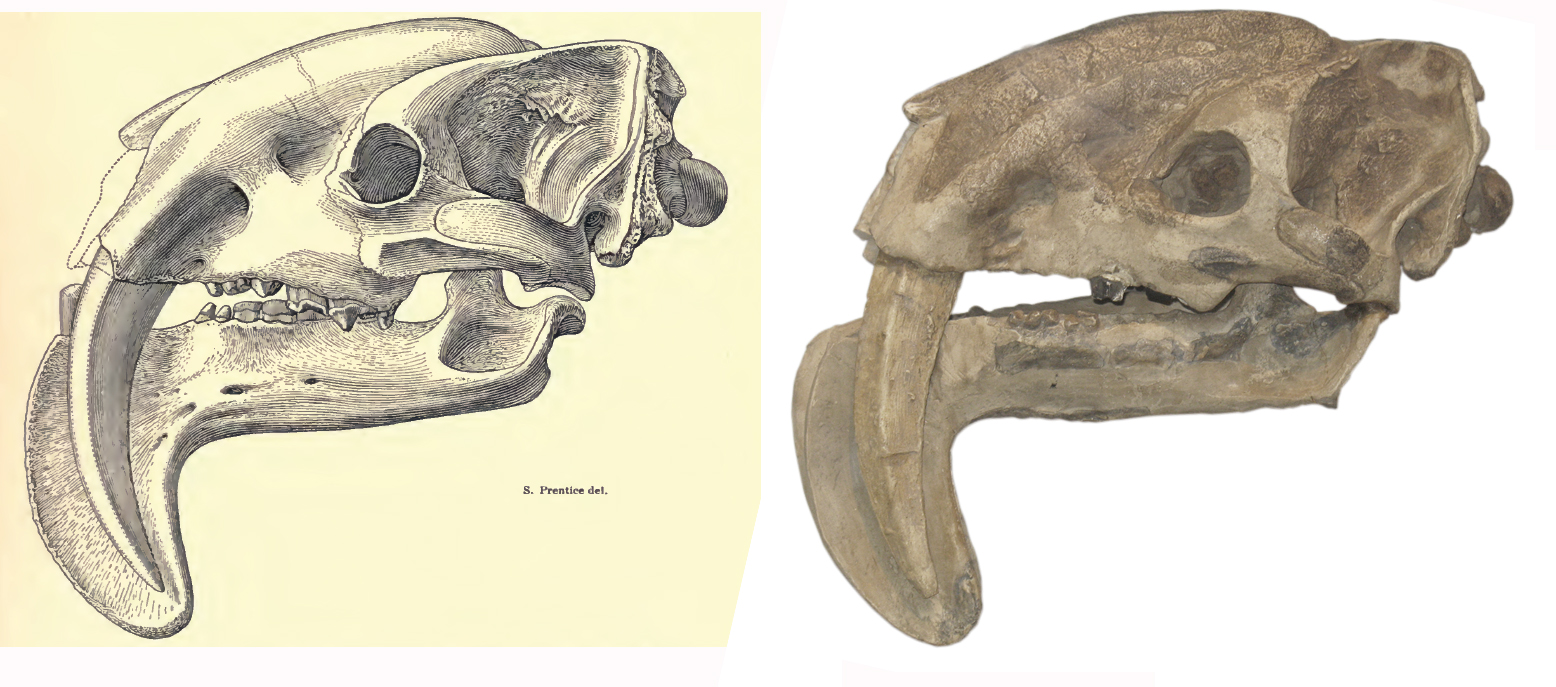

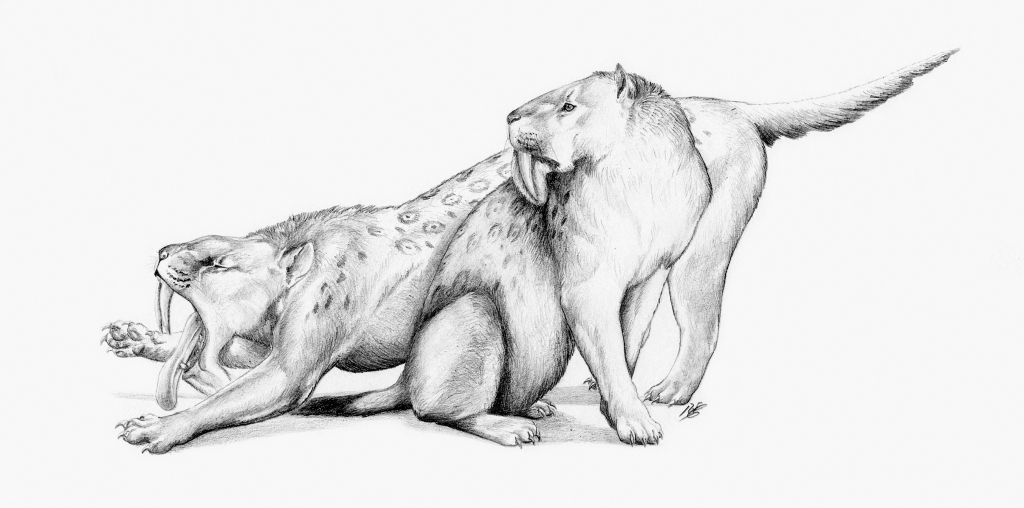

On the other side of the Pacific Ocean and much further back in time we have the intriguing animal known as the pouch knife. Superficially resembling a sabre-tooth cat, the low-slung pouch-knife was actually a marsupial and it possessed some of the most impressive canine teeth that have ever sprouted from the mouth of an animal, before or since. Known only from a few bones unearthed in Argentina in 1926 experts have pondered how this animal used it enormous teeth and the protective flanges on the mandible. One of the more outlandish theories proposed the teeth and flanges were used like can-openers to cut open the carapace of the extravagantly protected glyptodonts that lumbered around South America. More likely, the pouch-knife probably used its formidable teeth to pierce the tough hide of other South American mammals to severe important blood vessels.

The animals above and more than 60 others can be seen in the book: Extinct Animals An Encyclopedia of Species that Have Disappeared during Human History (by Ross Piper with illustrations by Renata Cunha and Phil Miller):

Leave a Reply